Michael* was nearing the end of his university degree at one of Australia’s top universities and was looking for internships so he could line up a grad role (or two) for when he finished his studies.

I asked him, “What sort of roles are you considering applying for? What do you want to pursue career-wise now that you’re about to graduate?”

Michael wasn’t sure:

“To be honest, I don’t really know what I want to do long term. I’m thinking of management consulting or trying to get into investment banking. I think both of these will give me the most options for my career over the long term.”

As humans, we freaking love having options.

- At school, we spend time trying to get ‘options’ for university.

- When we graduate from university, we want ‘options’ for our career.

- We want to be able to have ‘options’ for where we live, what we eat, where we holiday and who we date.

We are attracted to the idea of having choice. I know there is something deep within me that I cannot explain that LOVES having the freedom to choose from a range of options.

We feel in control when we have a choice.

In a world with increasing uncertainty and rapid change, having options also seems safe and the smart thing to do. If your career and industry become disrupted by technological advancement or external events, you are not screwed. You can pivot, and land on your feet in another one of your ‘options’.

Having options, therefore, appears to be strategic and it’s this perception that I believe is playing a key role in driving a growing phenomenon of our most smart, ambitious and driven young people en masse pursuing careers with consulting & professional services firms.

Upon graduating from university, still unsure of a single path to pursue, consulting provides the allure of options maximisation (and a nice paycheck).

You get the opportunity to work with a range of clients, in a range of industries, on a range of problems. You can do rotations across different groups. All of this ensures that you develop a wide range of skills, experiences and a network that keeps your options open for your next career move.

All of this seems smart. But is it?

Counterintuitively, pursuing career options may be the worst possible strategy.

(1) When we have options we find it more difficult to make choices.

The now-famous Jam study conducted in 1995 by Sheena Iyengar, a professor of business at Columbia University illustrates both our love of choice, but also its impact on our decision making.

Iyengar and her research team set up a booth of jams at a gourmet market. Every couple of hours they switched the selection of jams available for purchase from 24 jams to only 6 jams. On average, customers sampled two different jams, regardless of the assortment size on display.

Interestingly, 60% of customers were drawn to the stall when the larger assortment of 24 jams was on display (showing our predilection for choice), while only 40% stopped to look at the 6 jams.

The kicker however was that 30% of people who sampled from the small assortment of 6 jams, made a purchase, while only 3% of those who sampled from the assortment of 24 jams purchased a jar.

What this indicates (and has since been replicated in further studies) is what is known as the Paradox of Choice.

We want more choices, but the more choices we are provided with, the more difficult it becomes for us to make a decision.

(2) The consequence of options is that it leads to the trend of ongoing deferral of decision making and ongoing option maximisation.

When we don’t know what we want (or perhaps are fearful of making a commitment to something that we hear in our heart, or feel in our gut), we instead cultivate multiple options, and then struggle to make a decision.

This is known as decision paralysis and often occurs when you have to select from options that are hard to compare. Different career pathways fall squarely into this criteria.

This can result in procrastination and decision deferral (and often a lot of anxiety about the decision along the way)

When we do make the decision, it can however also mean that we take up an opportunity, not because it’s actually what we want to do or what our gut tells us we should pursue, BUT because out of all the options we have in front of us, it’s the one that will give us the most options for the next time around.

Options therefore can easily become an end unto themselves where we are choosing an option, because it will give us options.

(3) Having more options also lead to lower levels of satisfaction.

This might seem surprising and counter-intuitive.

Regardless of what we choose, when we’ve had multiple options laid out in front of us, we feel the opportunity cost of our decision more acutely.

Opportunity cost refers to the forgone benefit that you would have received by the option not chosen.

So when we pick one option, we feel FOMO (fear of missing out) for all the other options that we could’ve picked. This can then lead to something known as “Post Decision Dissonance” (PDD).

Yes, PDD is a real thing. Essentially, it’s the worry and regrets we feel that perhaps we didn’t make the right choice.

We’ll feel greater levels of PDD when the decision we had to make was very important, AND when the chosen and unchosen options all had high net desirability.

Choosing which university to attend, or choosing which career option to take are the sort of decisions that fall into this category of ‘very important’ and often have multiple ‘high desirability’ options.

So in other words, the better we become at creating multiple options for ourselves, the higher the levels of post-decision dissonance, and regret we feel when we make a choice.

(4) Having more options can lead us to trick ourselves that we want something.

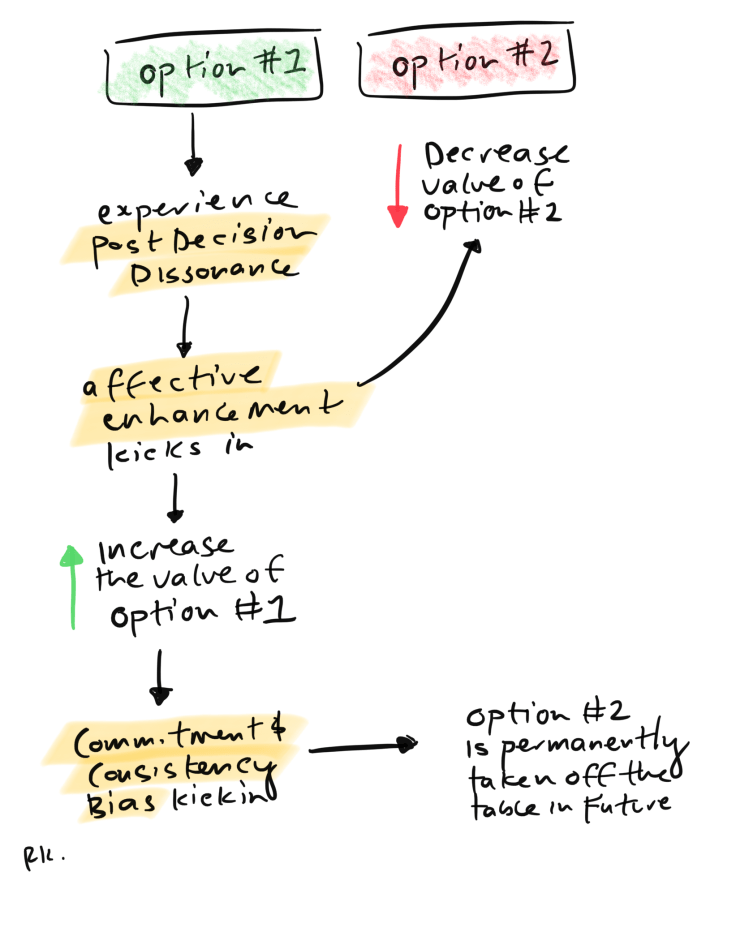

Over time, something else can also happen as a result of Post Decision Dissonance, and this is known as affective enhancement.

Let’s say you’re faced with a decision in relation to your career. You’ve got two options in front of you:

- Option 1: You’ve got an offer to work at a top tier consulting firm. The pay is great, and you’ll get to work on interesting projects. It also gives you lots of optionality in your career moving forward.

- Option 2: You can start your own company. You get to work for yourself, define your own schedule, and do something you are passionate about. You’ve got less optionality moving forward, however, as you’re putting everything on this bet, and there’s no certainty of what you’ll earn.

Let’s say, you decide to take Option 1. It’s a tough decision as you feel strongly pulled to do your own thing, but the safety, security, and optionality of consulting wins the day.

Because it was a tough decision, with high desirability in both options, you feel PDD. As you’re working at the office in the big top tier consulting firm, the feeling of regret and worry hits you. You start to feel anxious.

After some time passes, however, something changes.

When you talk about the decision with peers and friends, you start playing up why it wasn’t the right time to start your own company, why the company would’ve failed, and the size of the risks you would have had to take. You also start to emphasise the benefits of working at a top tier consulting firm, the projects you’re working on, and the benefits you’re receiving.

This is affective enhancement at play. Essentially, when we’re faced with making a decision like the above, to help us live with it, we begin to increase the value over time of the choice we made and devalue the option you passed on.

While this can help our levels of anxiety and mental health in the short term, it does have a dark side.

So we can live with ourselves our brain essentially has tricked us into believing that the choice we made and what we are doing right now is actually what we really wanted all along.

By also intentionally devaluing the option we didn’t take, it also makes it seem like a BAD choice (despite perhaps it actually being a fantastic one). By making it a bad choice, it also then discourages us from making this choice in the future.

This is compounded by commitment & consistency bias. As humans, we have a strong tendency to act according to the prior commitments we’ve made. Because Option 2 in our mind is now a bad choice, we act consistently with this belief in the future, and it becomes harder and more difficult for us to take that option when it presents itself again.

(5) Having multiple options hedges risk, but it also caps your upside.

When you create multiple options for yourself, this helps minimise risk. If the economy changes, or technology disrupts an industry, you have options in front of you to choose a pathway that will protect you. This is smart.

On the flip side, however, it also caps your upside.

Choosing consulting (Option 1 from above) for example provides you with lots of options moving forward, and it provides you with the security of knowing that you’ll earn good money and have career progression.

But at the same time, your upside is capped.

You know with fairly good clarity and certainty what the maximum is you’ll be able to earn in your career and what your career progression may look like.

You know with fairly good clarity and certainty what the maximum is you’ll be able to earn in your career and what your career progression may look like.

So picking consulting will minimise your downsides and risk while capping your upside.

This can be a good thing if you’re later on in your career and you have lots of responsibilities.

If you’re younger, however, ideally you should be taking more risks. You’ve got more time to recover and try different jobs and careers.

This is like the idea that if you’re investing in the stock market, based on your age (and therefore risk profile) your portfolio structure will vary. If you’re younger you should invest in higher-risk stocks, while if you’re older, you should place more in less risky asset classes like bonds and gold.

(6) Having multiple options can create less focus and consequently less success.

Generally speaking the most successful people in a career or industry are also those that are often the most focused.

Daniel Goleman, a globally re-known psychologist identifies that focus is the hidden driver of excellence. With focus, you can put all your energy into a single direction and this will enable you take advantage of the power of compounding.

I’ve written a lot about the importance of focus here.

In short, success and focus are directly correlated. The more focus you can bring to bear on a project or career, the more success you will experience.

And that’s why cultivating options is dangerous. Once again, it minimises your downside risk because if one thing you are doing doesn’t go well, you’ve got others to pursue, but it MASSIVELY caps your upside in the success you can achieve because you’re energy is not targetted.

And that’s why cultivating options is dangerous. Once again, it minimises your downside risk because if one thing you are doing doesn’t go well, you’ve got others to pursue, but it MASSIVELY caps your upside in the success you can achieve because you’re energy is not targetted.

(7) Having options lead to less creativity.

A review of 145 empirical studies on the effects of constraints on creativity and innovation found that individuals, teams, and organizations alike benefit from a healthy dose of constraints.

This is where the power of constraints (or having less options) are very powerful.

The review of the 145 studies revealed that:

“When there are no constraints on the creative process, complacency sets in, and people follow what psychologists call the path-of-least-resistance – they go for the most intuitive idea that comes to mind rather than investing in the development of better ideas.

Constraints, in contrast, provide focus and a creative challenge that motivates people to search for and connect information from different sources to generate novel ideas for new products, services, or business processes.”

In other words, having fewer options, and perhaps a single thing to focus on can foster greater levels of motivation, and higher levels of innovation, two things that are important in accelerating your career.

So, is maximising options a good thing?

In the short term, sure, but I think it ends up becoming a slippery slope.

None of this is to say that working in consulting or professional service firms are a bad thing. They offer incredible opportunities, training, mentorship and experience and provide lots of options for career growth and stepping stones.

The challenge is that once you have options, it becomes challenging to navigate, and doesn’t necessarily lead to achieving your best.

This, in turn, creates the risk that we end up however with a generation of some of our brightest young minds en masse becoming consultants, rather than choosing to work on more meaningful, pressing challenges that as a society we need to solve.

Right now, with the scope of national and global challenges we face as a species, we need young people to make BOLD choices in their careers.

So, how should we navigate the tension between having options vs focusing in our career?

Step 1: Recognise that choosing a career that maximises ‘options’ is the lazy choice

I think the first thing here is a mindset shift away from seeking a career that will ‘give you options’ if you don’t have clarity on what you want to do.

Finding clarity on what you want to do with your career is HARD and it often takes time and experimentation.

Simply settling on ‘consulting’ because it will give you options is the lazy choice.

Not only does it not necessarily answer the question for you (as it can lead to the ongoing deferral of decision making and self-deception about what we want) it also places the onus on ‘consulting’ or ‘investment banking’ as the solution to getting exposure to different opportunities to find your career clarity.

This often results in you not taking the responsibility yourself to do the hard work, soul searching and experimentation required to really find your ideal match quality, which is the degree of fit between your abilities, interests and the work you do, which is the key determinant of your level of fulfilment and performance.

Step 2: Understand career risk and place larger career bets when you are young

The second thing I think is to get more clarity and comfortability around the idea of career risk, and how your risk profile should look for your career based on your age.

Career risk refers to the chance your long term career will be negatively impacted.

When you’re young, you should take career risks and place some big career bets. This is the best time to do so because it gives you a higher likelihood of longer-term outsized success. You’ve got more time to work on a problem than others.

You’ve also generally got the least personal responsibilities in your life. You might still be living at home, and it’s unlikely you’ve got a family to support.

Placing big bets when you’re early in your career also however gives you time if things fuck up to start again.

As you get older, however, your career risk profile should change.

As you take on greater levels of personal responsibility (e.g. mortgages, family etc), you should be placing less risky bets in your career, and you should start to introduce an element of protection for the downside.

While this of course might cap some of your upsize, if you’ve placed your bigger career bets when you were earlier in your career, you should have already (hopefully) reaped some rewards, meaning that now, while you’re still growing your career, it’s the time to become a little more conservative.

So in short, when you’re early in your career, you should seek to maximise your upside, and as you progress through your career, transition over time as your responsibilities increase to protecting for your downside.

This is where if we consider consulting as an early career decision, it caps your upside, at a time when you should be taking bigger, bolder career bets.

Step 3: Use constraints strategically to get the most out of your options

Finally, if you do still decide to pursue a career in consulting (or something similar) straight out of university, there are some things you can do to minimise the negative consequences of ‘having options’

The first thing is to put a hard time end in advance on your career in consulting. This means, identify in advance how long you will stay in consulting. E.g. 12 months, 24 months, or 36 months (recommended absolute maximum).

Why?

If you’ve chosen consulting because you don’t know what to do, and you feel it will give you options, the purpose of being a consultant, therefore, should be about giving you enough exposure to a range of problems and industries so you can make a more informed decision about your ideal match quality.

The goal isn’t to be a consultant, it’s to optimise for the right amount of time you need to experiment (which consulting can support you with) so you can find your direction. Ideally, you want this time to be as short as possible because it’s eating up precious early-career time where you should be placing bigger, more ambitious bets.

The risk however is that picking a career for options tends to lead to that slippery slope of decision deferral and ongoing options maximisation. This means it comes with a high risk you get stuck and continue to seek options maximisation strategies in your ongoing career decisions.

The risk however is that picking a career for options tends to lead to that slippery slope of decision deferral and ongoing options maximisation. This means it comes with a high risk you get stuck and continue to seek options maximisation strategies in your ongoing career decisions.

I’ve seen this happen with so many peers and friends who started out in consulting because they didn’t really know what they wanted to do, and 10 years later, still hadn’t made a change, as they felt the same level of anxiety around what they should do with their career (which was compounded by their growing levels of personal responsibility)

By putting a hard end time on your career in consulting in advance (with a fairly short time horizon), the constraint, therefore, increases your motivation to ambitiously and proactively experiment and test what will be the best match for you + where you should place your bigger career bet while you’re still young.

It also acts as a circuit breaker to the risk that you fall into decision deferral as it forces you at a certain date to place a new career bet that will be in better alignment with your increased knowledge on your match quality and your career risk profile.

Conclusion

In short, be bold with your career choices.

Don’t optimise for options while you are young. Take career risks, and place career bets.

The world right now faces so many challenges, and we need young, bright, driven people to dive into work towards solutions.

We need you to be bold, and brave.

There’s always time as you progress through your career to become a consultant if you really want to. And, you’ll actually be better at it anyway then, as you’ll have more real-world experience you can bring to the table.

PS. *Michael is a pseudonym.